Summer Reads 2025: Princeton professors share what's on their lists

Six Princeton professors talk about favorite books and share what’s on their summer reading lists — novels, biographies and memoirs, fantasy, history and more.

This summer’s mix includes an epic family saga from Georgia (the country), a sci-fi trilogy, a Delaware River journey, a history of military hubris from Troy to Vietnam, two new books focused on the people behind artificial intelligence, and current science about our gut biomes.

Yelena Baraz

Yelena Baraz

Baraz is the Kennedy Foundation Professor of Latin Language and Literature and professor of classics. Her current book project is a joint translation of Ovid's “Metamorphoses” with her former Princeton colleague Jhumpa Lahiri.

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

“The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus” by Paul Zanker is about how art and architecture under the rule of Augustus, the first emperor of ancient Rome, was shaped not only by the people who created it, but by political and social forces of the time. I use this book in my teaching as a powerful way to convey those ideas to students, to open up the possibilities of how to think about creative and social processes.

What’s on your summer reading list?

“The Eighth Life” by Georgian writer Nino Haratischvili. I love to read translated fiction and novels about places I want to know more about. This novel was written in German, then translated into Georgian, then English. It’s an epic family saga (944 pages!) but you also learn a lot about the history of Georgia, a country I first visited in 2019 and loved.

“Babel: An Arcane History” by R.F. Kuang. This is for a mini book club with my 16-year-old twins. This historical fantasy novel is about empire, language and translation. Kuang also has a new novel coming out Aug. 25 called “Katabasis,” which is an ancient Greek word for going to the underworld. We’ll read that, too.

“Parade” by British novelist Rachel Cusk. Her writing is really sharp. I loved her Outline trilogy. The first book in that experimental trilogy is plotless, organized around conversations the main character has with people she encounters on a trip. “Parade” has been described as doing to character what “Outline” did to plot. I'm not sure quite what that means, but I know it will be interesting!

“The Rhetoric of the Body from Ovid to Shakespeare” by Lynn Enterline. I’m reading this for my translation project with Jhumpa. Ovid’s epic is about transformations of all kinds. Enterline’s book is explicitly about violence, what it does to our bodies and identities, and how Renaissance writers take up Ovid’s ideas in their own work.

“Tiberius and His Age: Myth, Sex, Luxury, and Power” by Edward Champlin. This book about the wildly reviled second Roman emperor was written by my former Princeton colleague, Ted Champlin, who passed away in January. When Ted became unwell and couldn't continue working on the book, another Princeton colleague and friend, Bob Kaster, worked with him to finish it. It’s filled with new and exciting ideas.

John Brooks

John Brooks

Brooks is assistant professor of molecular biology. His research focuses on how the circadian clock interfaces with the immune system to maintain harmony with the gut microbiome.

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

“I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life” by Ed Yong details our understanding of the microbiome and the beneficial bacteria that live on and within us. He puts the work of leaders in this field in a beautiful, descriptive format for a lay audience to understand. He demonstrates why our previous assumption that “all bacteria are bad and we need antibiotics to get rid of them” is not true and that the conversation our bodies have with bacteria is more dynamic and intricate.

What’s on your summer reading list?

“The Broken Earth Trilogy” by N.K. Jemisin. I really enjoy sci-fi and often listen to audiobooks in the lab, usually when I'm doing a lot of pipetting and repetitive tasks. If people see my headphones on in the lab, they know “Oh, John’s reading.”

In this trilogy, the Earth is in flux, but there are individuals called Orogenes who have the ability to quell the storm. The first book follows one Orogene and her relationship with this ability, which is frightening but also provides safety. It’s a beautiful mother-daughter story — if you’re an Orogene, your children usually are too — but I don’t want to say anything more.

“Days at the Morisaki Bookshop” by Satoshi Yagisawa. I’m going to Japan for the first time this summer and wanted to read a book to help me understand a little bit about Japanese culture. In the first three pages of this novel, a woman learns that the man that she's dating is leaving her for another woman and immediately getting married. She moves in with her uncle, who lives above his bookstore in Tokyo. Through reading books on grief and healing, she begins to heal. When Part One ends, she leaves the bookstore, ready to go back into the world.

“Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less” by Greg McKeown. I read this book over and over again. It lays out how to identify the most essential elements of the things that you need to be doing and how to prioritize those. I listen to this typically when I'm on a plane, when I’m away from the lab. It requires me to reevaluate the things I need to be most focused on and how to stay focused on them.

Yiyun Li

Yiyun Li

Li is professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts. Her memoir “Things in Nature Merely Grow” was published May 20.

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

“Housekeeping” by Marilynne Robinson. I think she is a superb writer and one of the most important living authors in America. “Housekeeping” is a 20th-century classic of American fiction. I teach this book every year in all my classes, because it's a book that needs to be read very slowly, line by line, word by word. That is a skill I think that Princeton students don't necessarily have, at least coming into my classroom.

I have students who say they can read 100 pages an hour, but I tell them, that’s not what I want you to do, I want to teach you how to read slowly and carefully. “Housekeeping” is about 200 pages, 11 chapters. I assign a chapter a week, and ask the students to notice five things about the chapter and write a detailed commentary. When reading slowly, students notice unusual wordings or a curious repetition of a phrase, which lead them to ask good questions and also think through a few thoughts.

“Housekeeping” doesn’t really have a plot. There are two girls who are orphans and their aunt. It's a novel about existence, about life lived in a detailed way: weather, nature, food, loneliness, solitude. The readers live through the novel with the three characters, whose thinking, feelings and perceptions become our own.

What’s on your summer reading list?

I read “Moby-Dick” and “War and Peace” once a year. (I just finished “War and Peace” with my students this spring, so this summer it’s time to start “Moby-Dick.”) People always ask me why. The book is always the book, but every time I read it, I'm a different person.

Also, part of my professional memory is saved in my copies of both books because I write comments in the margin. Every time I read, I notice new things. “War and Peace” is realism at its best. “Moby-Dick” is metaphor at its best. Together, these two books make a whole world. Together they make a more expansive world for me.

“The Book Against Death” by Elias Canetti. Starting in 1937, Canetti, who was born in Bulgaria but moved to Vienna as a child, kept notes on his thoughts for 60 years. The book is a collection of his thoughts, year by year. I like to read people's notebooks. I also like the title. That's quite a strong title.

“George Sand: A Biography” by Curtis Cate [1975, available as a used book and in library collections]. This one’s for research. I'm working on a trilogy of novels set in late 18th century/early 19th century Europe. Part of my character's history overlaps with George Sand's history in France, so I'm reading her biography to get a sense of France at that time.

“A Truce That Is Not Peace” by Miriam Toews. This memoir is coming out in August. Toews quotes a few lines from one of my books, so I have an advance galley. She lost her father and her sister to suicide, as I lost my children to suicide. In a sense, we both write about the world from a very strange place. I’m going to reread her novel “All My Puny Sorrows” after reading her memoir — the novel is quite autobiographical, about her sister’s death.

And finally, the entire body of work by Camus. I wrote about Camus a lot in my new memoir. My son James loved reading Camus so, I think, "Well, this summer, I'm just going to read Camus." I live by reading.

Stephen Macedo

Stephen Macedo

Macedo is the Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Politics and the University Center for Human Values. His book “In Covid’s Wake: How Our Politics Failed Us,” co-written with Frances Lee, was published March 11.

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

“The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam” by Barbara Tuchman explores the foolish errors that governments and leaders have made across the centuries, persisting in misguided courses of action that many people at the time saw to be wrongheaded. I love Tuchman's writing. She does her homework and displays insight into human character.

What’s on your summer reading list?

Two very recent books may help those of us who want to reflect on what the pandemic reveals about our politics:

- David Zweig’s “An Abundance of Caution: American Schools, the Virus, and a Story of Bad Decisions” discusses the flawed decision-making around school closures in the U.S. There was a great deal of evidence from Europe by May 2020 that schools could reopen safely, but it was ignored. Zweig’s is an earnest, sober book, telling an important story, and I strongly recommend it.

- In Jacob Hale Russell and Dennis Patterson's recent “The Weaponization of Expertise: How Elites Fuel Populism,” the authors acknowledge we need experts, but they point out the dangers of elites’ not trusting the public and not telling the whole truth, especially when it’s complicated. Experts should inform us but cannot tell us what to do.

Two very readable books help explain some larger aspects of the plight of American politics today:

- “Let Them Eat Tweets: How the Right Rules in an Age of Extreme Inequality” by Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson shows how much greater inequality has become in the U.S. as compared with many European democracies, and the increasing temptation of the very rich to subvert democracy to keep power.

- “The Great Exception: The New Deal and the Limits of American Politics” by Jefferson Cowie focuses on the most egalitarian period in U.S. history, from the New Deal of FDR through Lyndon Johnson's Great Society. He argues that the immigration restriction laws of the early 20th century — which cut immigration to the U.S. by 85 or 90% — helped make working class people more united in support of an expanded social welfare state. The upshot is that it may not be politically possible for progressives to achieve everything they want: open borders, increasing diversity, and the social solidarity that we need to sustain welfare programs. I'm drawn to books that challenge orthodoxies, and this is one.

Finally, for something hopeful about the possibilities of American political life:

“Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt” by H.W. Brands is a fascinating account of one of our greatest presidents, who confronted two great national crises: the Great Depression and World War II. This book reminds us that real progress can be made even in a country as big, diverse and difficult to govern as the U.S., when we are lucky enough to have leaders with both moral and political sense. And I guess I need to add that FDR had for a time huge majorities in both Houses of Congress, and that sure helped too.

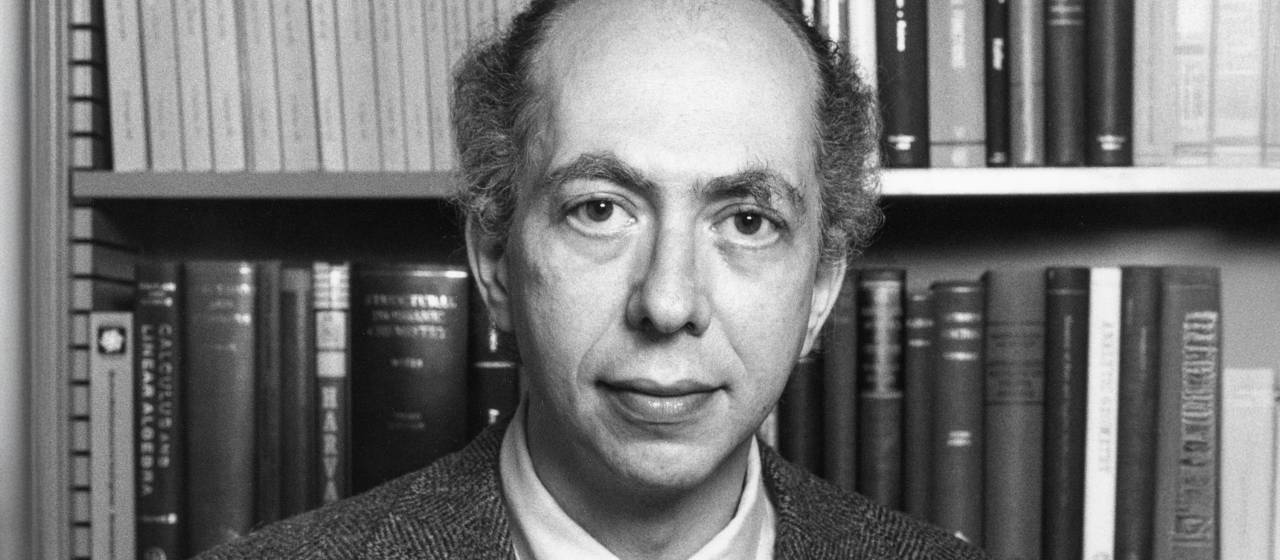

Arvind Narayanan

Arvind Narayanan

Narayanan is professor of computer science and director of the Center for Information Technology Policy. His book “AI Snake Oil: What Artificial Intelligence Can Do, What It Can’t, and How to Tell the Difference,” co-written with Sayash Kapoor, was published Sept. 24, 2024.

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

“The Politics of Evidence: From Evidence-Based Policy to the Good Governance of Evidence” by Justin Parkhurst. I teach this in a course called “Science for Policy and Policy for Science.” It takes the debate about the proper place of science in policy that has often rocked our society — with a lot of people feeling that policy should be much more science-based and evidence-based, and other people having a negative reaction to certain ways in which science has influenced policy — and gives us concrete concepts to put these concerns into words.

I’m a scientist who often advises policymakers, and this book has allowed me to think about this in a much more sophisticated way that respects differences in values and doesn’t trigger backlash. I felt that was an important insight for my students as well.

What’s on your summer reading list?

“Lovely One” by Ketanji Brown Jackson. She is such an inspiring figure. I'm looking forward to the blend of memoir and incisive commentary about the country. Another aspect I’m drawn to is overcoming adversity, which is a big theme of this new memoir.

“Not the End of the World: How We Can Be the First Generation to Build a Sustainable Planet” by Hannah Ritchie offers a completely new way to think about sustainability. Ritchie says technology can actually be a good thing for sustainability, and that sustainability can't only be about environmental impact. We've never been at a level where we could achieve our goals for human flourishing in a way that would also achieve [sustainable] environmental impact. But she lays out a way to achieve those goals simultaneously.

“Invisible Rulers: The People Who Turn Lies Into Reality” by Renée DiResta is about misinformation and conspiracy theories on social media. DiResta is a colleague at Stanford University who was herself a target of a conspiracy theory, so she blends her expertise with her own personal story in talking about this very tricky subject and how social media leads to amplification of some of those narratives.

I have two books about AI: “Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI” by Karen Hao and “More Everything Forever: AI Overlords, Space Empires, and Silicon Valley's Crusade to Control the Fate of Humanity” by Adam Becker.

There are two ways of looking at historic changes. One is that they're driven by people in power — the Sam Altmans of the world in the case of AI, and the other is that they’re the inevitable result of large-scale technological, structural and political shifts, and are not so much about the individuals. I think there is merit to both views.

As a computer scientist, I naturally inhabit the latter. So, it's interesting to read the other perspective and to think about how things could have gone differently if there were a different decision-maker in a position of power. These are both stories about the people behind AI and not only the technology itself.

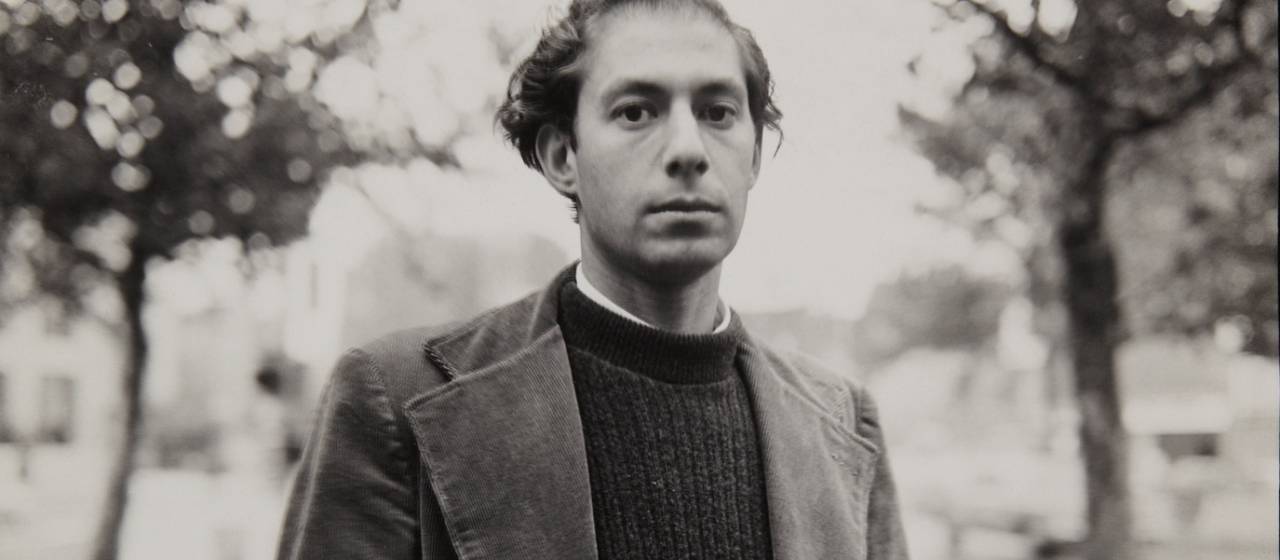

Sara S. Poor

Sara S. Poor

Poor is associate professor of German. Her current book project “The Literary Agency of Medieval Women: Kunigund Niklasin and the Library of St. Catherine's in Nuremberg,” is forthcoming from Oxford University Press (summer 2026).

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

“Nature's Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard” by Doug Tallamy. The nature preserves and open spaces in the U.S. are not enough to support our bird/insect ecosystem — with the number of species rapidly declining in the last 50 years. Tallamy started a movement, Homegrown National Park, to encourage people to plant even a few native plants in their backyard, creating “stop-overs” for migrating birds and monarch butterflies and homes for insects.

My garden is 80% native plants. On campus, it makes me so happy to see the native plants surrounding new and renovated buildings, including Firestone Library, the art museum and Stadium Garage. In fall 2023, I taught a Freshman Seminar at New College West. On the way to the first class, I came upon their meadow full of beautiful native grasses (big bluestem and switchgrass), blooming New England asters, and a gorgeous little yellow flower called beggarticks. Watching the bees in the flowers almost made me late for class.

What’s on your summer reading list?

“Borne by the River: Canoeing the Delaware from Headwaters to Home” by Rick Van Noy. I’ve always loved rivers. I went on canoe trips in the Adirondacks as a girl and rowed crew in college. This memoir traces the author’s 200-mile canoe trip down the length of the Delaware River, weaving in environmental history and his experience joining an annual canoe trip led by members of the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania.

“There Are Rivers in the Sky” by Elif Shafak. Another river book — a historical novel about the Tigris and the Thames.

I’m reading two books that I might add to the syllabus for my course called “Medieval Gender Politics: Wicked Queens, Holy Women, Warrior Saints”: “A Medieval Life: Cecilia Penifader and the World of English Peasants Before the Plague” by Judith Bennett and “A Poisoned Past: The Life and Times of Margarida de Portu, a Fourteenth-Century Accused Poisoner” by Steven Bednarski. We read about Eleanor of Aquitaine and Joan of Arc but students also asked to read about ordinary women and that’s what these books are about.

I’m reading two other historical books, which relate to my new book project. “Nails in the Wall: Catholic Nuns in Reformation Germany” by Amy Leonard is about the period right after my book ends, which I touch on in my conclusion. “The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu and Their Race to Save the World’s Most Precious Manuscripts” by Joshua Hammer is about the ancient Arabic manuscript culture in Timbuktu [a city in Mali], when shepherds would bury their manuscripts in a chest to protect them from marauders, and the archivist in the 1980s who traveled on camel to help rescue those manuscripts before the rise of al-Qaida.

“Johannes Gutenberg: A Biography in Books” by Eric Marshall White, the Scheide Librarian and Assistant University Librarian for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at Princeton. I'm excited to read this because Gutenberg was a frequent topic in a graduate seminar I co-taught with Eric in spring 2022 called “Middle High German Literature II: Fifteenth-Century Book Culture of the German-Speaking World.”

Latest Princeton News

- Warrior-Scholar Project 2025: 'Fueled by the pursuit and discussion of knowledge'

- Princeton tapped as partner for new NSF-funded AI Materials institute

- Neuroscientist Fenna Krienen named a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences

- Early quantum engineer Morton Kostin dies at 89

- Allen Rosenbaum, former director of Princeton University Art Museum with a keen curatorial eye and astute administrative foresight, dies at 88

- Experiential learning: Athens summer seminar provides transformative experience for FLI students