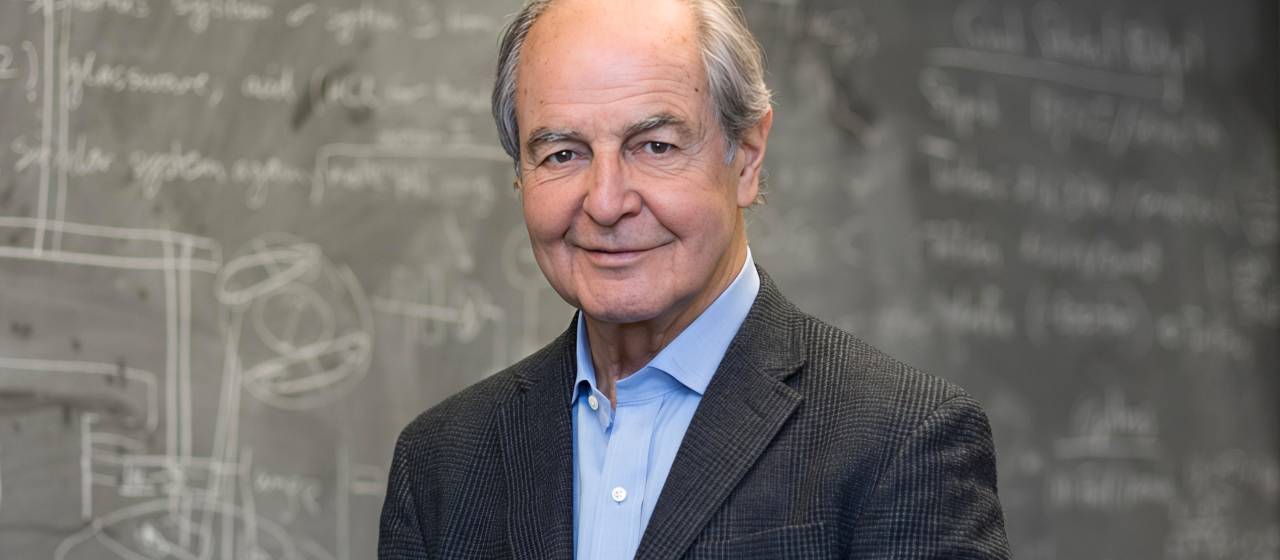

Physicist Frank Calaprice, leading neutrino expert and ‘tremendous mentor,’ dies at 85

Frank Paul Calaprice, an emeritus professor of physics, died on June 30, days before his 86th birthday.

Over the past 55 years, Calaprice’s research, discoveries, global collaborations, mentorship and teaching transformed the field of neutrino physics. Neutrinos, the smallest known particles, are produced by stars’ fusion, and were thought for decades to have no mass at all. Calaprice’s work contributed to overturning that assumption.

“Frank lived a very full life, which had a tremendously positive impact on many individuals, and also within his fields of study,” said Bruce Vogelaar, a former Princeton colleague who is now a professor of physics at Virginia Tech. “For me personally, he epitomized what a careful experimentalist with a deep appreciation and understanding of physics could achieve. He set the course for my career when he agreed to make me an assistant professor at Princeton.”

One of Calaprice’s first roles at Princeton was running the Princeton cyclotron lab, which he later co-directed with Arthur McDonald, the 2015 Nobel Prize laureate in physics.

Calaprice was "uncompromising in his scientific work and passed that approach along to several generations of students who were lucky enough to work with him. He was a great colleague and friend, and I have many fond memories of our association,” said McDonald, who taught at Princeton from 1982 to 1989 and is now an emeritus professor of physics at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada. “He always had excellent ideas for physics measurements at the frontiers of science and technology.”

Calaprice is perhaps best known as one of the leaders of the Borexino project, which involved burrowing under an Italian mountain, Gran Sasso, and filling a huge nylon balloon with fluid to detect neutrinos, so-called “ghost particles” that pass through us constantly but almost never interact with our bodies — or much of anything else.

Early setbacks revealed that the project needed a major redesign, and Calaprice became known for his unflinching insistence on “getting it done right,” even when it ruffled feathers.

Cristiano Galbiati, now a professor of physics at Princeton, was an undergraduate doing a one-year intensive at Gran Sasso while Calaprice was there for a sabbatical year. “It was a tough year,” he said. “Pressure was mounting: the solar neutrino problem was one of the hottest in physics, and everyone was eager to get our results soon,” he recalled.

Over the course of two years, he said, “Frank had almost entirely reshaped the design of the experiment. Frank fought endless battles — losing some, winning some, opening up new ones when needed — and did not quit until he thought the design of the detector was sufficiently resilient for success. The design was so strong that on May 1, 2007 — when the detector was just barely half-full — we started seeing a beautiful signal of neutrinos, the best and clearest ever recorded. It was a true triumph of Frank’s dedication and intellectual battle to redesign the experiment.”

Ultimately, Borexino had an onion-like structure with many layers of protection around its radioactively pure, hypersensitive core. It operated from 2007 to 2021, during which time it detected neutrinos from the Sun and others — geoneutrinos — that originate from radioactivity deep in the Earth. In addition to capturing solar neutrinos generated when two hydrogen protons fuse to make helium — known as pp fusion — Calaprice and his colleagues documented the electron-capture decay of beryllium-7, the three-body proton-electron-proton (pep) fusion, and boron-8 beta decay.

Calaprice fought for improvements that created the amazing degree of purity needed in the “scintillator” — the fluid in the core — that was sufficient to reveal even the carbon-neutron-oxygen neutrinos (known as CN or CNO neutrinos) that make up less than 1% of the Sun’s neutrino emissions. “Running in these improved conditions enabled the first measurement of the reactions creating these elements essential for life,” noted McDonald.

“His Borexino accomplishments — a measurement of all four neutrino sources from the pp chain as well as the CN neutrinos — will be in the textbooks a century from now,” said his colleague Wick Haxton, a professor emeritus at the University of California-Berkeley.

Tireless focus on expanding knowledge

“Neutrinos are elusive particles; detecting them is a bit like trying to isolate a handful of specific raindrops in the middle of a hurricane,” explained Laura Cadonati (Ph.D. 2001), who was one of Calaprice’s first graduate students and is now the associate dean for research at Georgia Tech’s College of Sciences.

“These ‘ghost particles’ stream from the Sun at 420 billion per second through every square inch on Earth, yet they’re nearly impossible to catch because they mostly slip through matter without leaving a trace. With Borexino, Frank built a detector that was so extraordinarily clean that it could isolate neutrinos from the ‘hurricane’ of environmental radioactivity — catch them and use them to give us a real-time view into energy production from the Sun. The techniques Frank pioneered for Borexino have set the standard for many other nuclear physics experiments.”

Like Galbiati, Cadonati met Calaprice in 1994 during his sabbatical year at the Gran Sasso laboratory. “Frank didn’t just teach me physics — he taught me that science is fundamentally about human connections and the courage to pursue what seems impossible,” she said. “It is because of what I learned from Frank and Borexino that I launched into my career pursuing an even more elusive signal, gravitational waves, which were considered impossible to detect but have now opened new windows on the universe. … I owe Frank not just my career, but my understanding that great science happens when brilliant minds refuse to accept limitations and have the courage to encourage others to pursue the impossible.”

A later graduate student, Andrea Pocar (Ph.D. 2003, now a physics professor at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst), added that Calaprice “directly trained or indirectly inspired a new generation of scientists in the field.”

Brooke Russell, a member of the Class of 2011 who spent years working with Calaprice on the Borexino project, was among them.

After doing her senior thesis with Calaprice, Russell continued as a postbaccalaureate researcher for two years. “In that time, Professor Calaprice gave me the confidence to pursue a career in physics,” Russell said. She went on to graduate school, becoming the first African American woman to complete a Ph.D. in physics from Yale. She is now an assistant professor of physics at MIT. “Objectively, he changed the trajectory of my life.”

“Frank was a wonderful mentor, who was always willing to go above and beyond,” said Jingke Xu, who completed his Ph.D. in 2013 as one of Calaprice’s final graduate students and is now a physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. “When I joined Princeton in 2008, I was ambitious and yet clueless about physical research. It was Frank who taught me about neutrino and dark matter physics, trained me with niche experimental skills, and inspired — or enabled, if it is not too strong — me to pursue a career in science.”

Calaprice first enrolled at Pasadena City College, then earned both his B.A. (1961) and Ph.D. (1967) at the University of California-Berkeley. When finishing his postdoctoral research, also at Berkeley, Calaprice joined Princeton’s faculty in 1970 as an assistant professor of physics. He was promoted to associate professor in 1977 and to full professor in 1980.

His early work had centered on the study of time reversal invariance in decays of polarized noble gas atoms, resulting in his developing the most sensitive test for time invariance in nuclear beta decay, the gold standard for more than 20 years. His later work focused on finding more and more ways to improve the neutrino-detecting capabilities of Borexino.

Most recently, Calaprice played a crucial role in two dark matter searches: the DarkSide program for searches with underground argon and the SABRE program for searches with sodium iodide detectors.

He transferred to emeritus status in 2018, then held the position of senior physicist until 2022.

Among his many awards are an Engineering Council Excellence in Teaching Award, for which he was nominated by his students, and the prestigious Hans A. Bethe Prize from the American Physical Society “for pioneering work on large-scale, ultra-low-background detectors, specifically Borexino, measuring the complete spectroscopy of solar neutrinos, culminating in observation of CNO neutrinos, thus experimentally proving operation of all the nuclear energy driving reactions of stellar evolution.”

Calaprice is survived by his former wife Alice, a noted Einstein biographer; a daughter, Denise, a 1995 Ph.D. graduate of Princeton who is now academic program adviser at Stanford University’s Pediatrics-Rheumatology program; a son, David, principal scientist at Adobe; a daughter-in-law, Lori; and his grandchildren Ryan, Chris, Emilia and Anya. View or share comments on a memorial page intended to honor Calaprice’s life and legacy.

Latest Princeton News

- Michael Skinnider wins 2025 Packard Foundation Fellowship

- A ‘town square for the arts and humanities’: The new Princeton University Art Museum shares opening details

- The ‘Many Minds, Many Stripes’ conference celebrating Graduate School alumni is underway on campus

- Society of Fellows in the Liberal Arts welcomes new scholars

- Princeton alumni Nabarun Dasgupta '00 and Sébastien Philippe *18 win MacArthur 'genius' grants

- Venture Forward gifts name multiple spaces within the new Princeton University Art Museum